Ducks quack primarily for communication. Quacking serves various purposes, like signaling distress, maintaining contact with the flock, and expressing emotions. Female ducks are typically louder and quack more often than males. The distinctive “quack” sound varies among species, reflecting differences in size, social behavior, and habitat.

| Type of Quack | Purpose |

|---|---|

| Basic Quack | Socializing, Location Signaling |

| Hail Call | Attracting Distant Ducks |

| Feeding Call | Signaling Safety, Social Feeding |

| Alarm Call | Warning of Danger |

| Mating Call | Courtship, Mating Signals |

| Maternal Call | Communicating with Ducklings |

| Agitated Call | Expressing Distress or Agitation |

In this article we embark on the exploration of why ducks quack, we uncover the layers of meaning behind each sound, delving into a world where each quack tells a story of survival, social interaction, and the innate behaviors of these intriguing birds.

Communication Among Ducks

Communication in ducks, primarily through quacking, is a sophisticated system that plays a crucial role in their social interactions and survival.

This section delves into how ducks use their varied quacks to communicate with each other, emphasizing the importance of these vocalizations in their daily lives.

Ducks are social birds, often found in groups or pairs, and their ability to communicate effectively is vital for maintaining these social structures.

The basic quack, commonly associated with female mallards, is a primary means of keeping the group together. When a duck gets separated from its flock, it uses loud quacks to signal its location, allowing others to respond and regroup.

In the context of mating, communication is key. During the breeding season, ducks use specific calls to attract mates and establish pair bonds.

The mating call, a unique quack used by females, signals their availability and readiness for reproduction. Males, in response, may perform visual displays or emit softer quacks to show their interest.

Mother ducks communicate with their ducklings through a series of soft, repetitive quacks. This maternal call is essential for the survival of the ducklings, guiding them through their environment, alerting them to food sources, and warning them of potential dangers.

The ability of ducklings to recognize and respond to their mother’s call is crucial from the moment they hatch.

Alarm calls are another critical aspect of duck communication. These sharp, loud quacks serve as a warning signal to other ducks in the vicinity, indicating the presence of predators or other threats.

The immediate response to these alarm calls, often a quick dispersal or a unified defensive action, highlights the efficiency of their communication system.

Furthermore, ducks have been observed to modify their quacks based on their environment. In noisy, urban areas, ducks might alter the pitch or volume of their quacks to ensure they are heard over the background noise, demonstrating their adaptability and intelligence.

Comparison with Other Birds

Ducks, known for their distinctive quacking, exhibit communication patterns that are both unique and similar to other bird species. This section compares the quacking of ducks with the vocalizations of other birds, highlighting the diversity and complexity of avian communication.

Unlike ducks, many bird species rely on a combination of songs and calls. Songs are typically longer, more complex, and are used primarily for attracting mates and defending territories.

Calls, on the other hand, are shorter, simpler sounds used for a variety of purposes, such as signaling danger or coordinating with the flock. Ducks primarily use quacks, which are more akin to calls in their brevity and functionality.

One notable difference is the vocal range. While some birds, like songbirds, have a wide range of melodious tunes, ducks generally have a more limited vocal repertoire. However, what ducks lack in variety, they make up for in volume and clarity, especially in the loud, echoing quacks of female mallards.

Another difference lies in the learning of vocalizations. Many songbirds are known for their ability to learn and mimic sounds, a trait not commonly observed in ducks. Ducks’ quacks are more instinctual and less varied, although there is evidence suggesting regional variations, akin to dialects.

Table: Duck Quacks vs. Other Bird Sounds

| Bird Type | Vocalization Type | Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| Ducks | Quacks (Calls) | Socializing, Alarm, Mating |

| Songbirds | Songs and Calls | Mating, Territory Defense |

| Crows/Ravens | Caws and Calls | Communication, Problem Solving |

| Owls | Hoots | Territory Defense, Mating |

This comparison shows that while ducks may not have the extensive vocal range of some birds, their quacking serves a vital role in their survival and social interactions, reflecting the diverse ways in which birds communicate.

Ducklings and Quacking

The relationship between mother ducks and their ducklings is intricately tied to the art of quacking. This section explores how quacking plays a pivotal role in the development and survival of ducklings, emphasizing the maternal bond and communication strategies.

From the moment they hatch, ducklings are attuned to the sound of their mother’s quack. This maternal call is crucial for the ducklings’ survival, as it guides them through various aspects of their early life.

The mother duck uses a series of soft, repetitive quacks to keep her brood together, leading them to food sources and away from potential dangers. This constant communication ensures that the ducklings stay close to their mother, especially in the first few weeks when they are most vulnerable.

The ability of ducklings to recognize and respond to their mother’s call is remarkable. Studies have shown that ducklings can identify their mother’s quack amongst a chorus of other sounds, a testament to the strong bond formed between them.

This recognition is vital, especially in environments where multiple duck families coexist, as it prevents ducklings from straying and following the wrong mother.

Moreover, the maternal quack serves as a teaching tool, helping ducklings learn the nuances of quacking and other behaviors essential for their growth and survival.

As they mature, ducklings begin to mimic these sounds, practicing their own quacks, which will eventually become their primary means of communication.

The Role of Environment in Duck Quacking

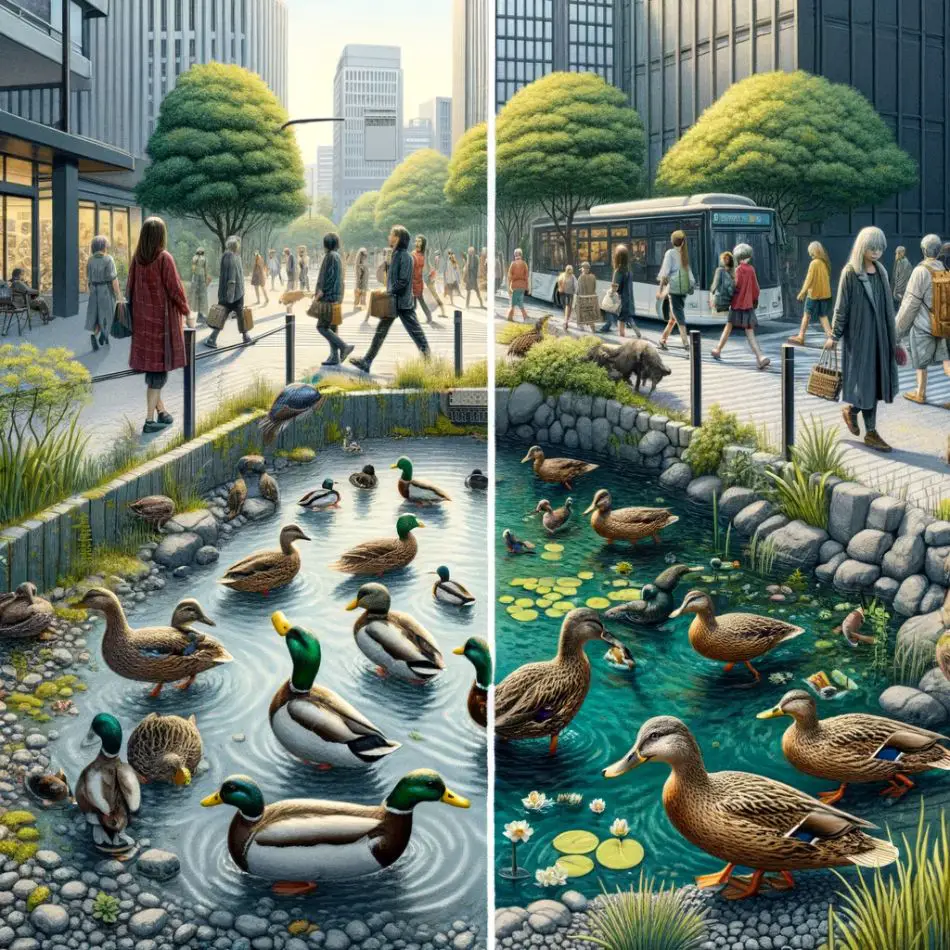

The environment plays a significant role in shaping the quacking behavior of ducks.

This section examines how different settings, from urban landscapes to rural wetlands, influence the way ducks communicate, highlighting their adaptability and the impact of human activities on their vocalizations.

In natural, quieter environments like rural wetlands, ducks’ quacks are typically used for routine communication such as signaling location, maintaining social bonds, or warning of predators.

The natural acoustics of these areas allow quacks to travel farther, ensuring effective communication over larger distances.

Contrastingly, in urban areas, where noise pollution is higher, ducks face the challenge of making themselves heard over the cacophony of city life. Studies have shown that urban ducks often alter their quacking in response to this.

They might increase the volume, frequency, or pitch of their quacks to cut through the background noise. This adaptation is a remarkable example of how wildlife adjusts to human-altered environments.

Furthermore, the presence of humans can also affect duck behavior and quacking. In parks and urban settings where ducks are regularly fed by people, they may become more vocal, associating human presence with food. This can lead to a change in their natural quacking patterns and social behaviors.

Environmental changes, such as habitat loss and climate change, also impact duck populations and their communication. The loss of wetlands, for instance, can lead to reduced breeding grounds, affecting the natural quacking behavior associated with mating and territorial claims.

Myths and Misconceptions About Duck Quacks

Duck quacks are surrounded by various myths and misconceptions, some of which have become quite popular in popular culture. This section aims to debunk these myths and clarify the facts with scientific evidence, providing a clearer understanding of duck vocalizations.

One of the most famous myths is that a duck’s quack doesn’t echo. This myth has been widely circulated, but scientific studies and experiments have debunked it. In reality, duck quacks do echo, just like any other sound.

The misconception may have arisen due to the unique acoustic properties of the quack, which might make the echo less discernible to the human ear.

Another common misconception is that only female ducks quack. While it’s true that the loud and familiar quack is most often made by female mallards, male ducks are not silent.

They produce softer, rasping sounds, which are less commonly recognized as quacks but are important in their communication, especially during mating season.

There’s also a belief that ducks quack more in the rain. However, there’s no scientific evidence supporting this. Ducks may be more active and vocal during certain weather conditions, but this is not specifically related to rain.

Lastly, some people think that ducks from different regions sound the same. Recent research, however, suggests that there can be regional variations in quacks, akin to dialects, indicating a more complex level of vocalization than previously thought.

By addressing these myths and misconceptions, we gain a more accurate and scientific understanding of duck quacks, appreciating the complexity and diversity of these vocalizations.

Conclusion

In exploring the world of ducks and their quacks, we’ve uncovered a tapestry of communication, behavior, and adaptation.

Understanding why ducks quack reveals much about their social structures, environmental interactions, and the challenges they face.

It’s a fascinating glimpse into the complexity and resilience of these remarkable birds.